David Lucas is an established picture book creator who draws many of his influences from folklore and myth from around the world. His book The Wonderbird will be published by Orchard Books. We talk with David about his book, and he shares thoughts on elements of folklore within modern life, philosophy, design, and storytelling.

Cover design, The Wonderbird, David Lucas.

GTP- So can you tell us a little about how folklore been a source of inspiration for you throughout your career?

DL- I spent half my time as a teenager skulking in my local library and I read every book I could find on folklore - books like Katherine Briggs' Dictionary of Fairies, and Frazers The Golden Bough. I was interested in Jung, and saw that the same motifs appear again and again in folk art and myths across the world. When I was 17 I bought this Sepik River carving of a crocodile creator goddess and put it above my bed. Currently it hangs over the staircase at home, scaring my 4yr old daughter. (I photographed it in the garden for better light.)

Sepik River carving of a crocodile creator goddess.

I became acquainted with outsider art as a student, when a college friend, Wilfrid Wood, went on a tour of the Deep South visiting outsider artists like Howard Finster, Mose Tolliver and R.A. Miller. Wilfrid is a friend of Jon Maizels who founded the magazine Raw Vision, and both collect outsider art. I see outsider art as spiritual art in an unspiritual age - hence its outsider status. It's no accident that so many outsider artists are preachers, or see themselves as prophets.

This is by The Rev. B.F. Perkins (1904-93).

Rev. B.F. Perkins (1904-93)

St. EOM (Eddie Owens Martin) was High Priest of his one-man religion, Pasaquoyanism. I see these kinds of marginal figures as standing in direct reaction to the drab utilitarianism of modern life, voices in the wilderness trying to tell us that they have glimpsed divine mysteries, that we aren't just machines, or robots (or 'chemical scum on a rock' as Stephen Hawking claimed).

Eddie Owens Martin

All traditional societies are religious, and folk art is ritualized, religious art, characterized by crisp line and flat colour, an emphasis on pattern over realism, and on figures as types rather than individuals. The folk artist and outsider artist have a shamanic role, channeling ancient stories and imagery, bringing them to new life in the present.

Folk art shows us a patterned, hierarchical world, a world oriented towards the gods, where the artist is embedded in community and tradition, and his or her duty is to re-invent that tradition from within, as the voice of the tribe.

This quilt, made in the 1850s by James Williams, a tailor from Wrexham, tells the story of his tribe (Welsh Methodists) and features Bible stories (Adam naming the beasts, Cain murdering Abel, etc.) alongside the very latest technology of the day: suspension bridges and railways. The quilt is a vision of an intricately patterned world, of completeness and wholeness, of old and new united, timeless and modern all at once.

It is my favourite British work of art of the 19thC - but it was made by an uneducated tailor, in his spare time, by candlelight, with whatever off-cuts he had to hand.

Quilt 1850s James Williams

GTP- Were there any specific folksongs, or folklore , or mythologies (from any country or tradition) that you are directly drawing upon when creating The Wonderbird?

DL- Birds and flowers are the two commonest motifs in all the folk art traditions around the world. Some of my favourite folk art images are the 'fraktur' pictures of Dutch and German Pennsylvania - decorative designs made to commemorate and sacralize a big family event, a marriage, or the baptism of a child.

'fraktur' pictures of Dutch and German Pennsylvania

Birds have always been imagined as messengers linking Heaven and Earth - which is why angels have wings, and why Hermes, as psychopompos, (leader of souls to the afterlife) had wings on his feet, and birdsong has always been seen as a language of prophecy and secrets.

Wonderbird Title Spread

But the legend that The Wonderbird echoes most closely is the story of the Phoenix. The Wonderbird is a giant flock of birds that is itself a bird, and to me it represents those rare moments of unity, when the individual really is in harmony with the group. Inevitably, moments of real balance and coherence are unsustainable, hard-won unity soon breaks down. The birds disperse, the Wonderbird fragments, dies and must be re-born, just like the Phoenix. The happy ending of the story is the Wonderbird living again, singing again.

Wonderbirds

You can think of it as the story of any tradition, blooming, fading and being born again, simultaneously new and not-new, ancient and modern.

Yuval Noah Harari says that modern society has traded meaning for power. As a society we have amazing technological capabilities, but we lack meaning, we are atomized individuals groping for connection to both nature and community, often groping for a real sense of purpose. Our society is the only atheist society that has ever existed - but human nature hasn't changed: we still need ritual, and belonging, and a vision of some sort of cosmic centre (a god) to orient ourselves towards. Our happiest moments are when we surrender to something bigger than ourselves, when we find meaning in becoming part of a crowd of like-minded 'believers', all facing in the same direction.

Groupishness is a potentially dangerous force precisely because it is so elemental, but it is morally neutral, like any force of nature. Fire in the wrong hands is dangerous, but harnessing fire was the beginning of civilization. We all want to belong, and belonging is a volatile energy source, that illuminates and inspires, while always having destructive potential.

The Wonderbird breaks up because one little bird, called Piper, starts asking questions: who is the Wonderbird, and why has no one ever seen her? Of course, they can't see her: they are part of her. They all fly off in different directions looking for the Wonderbird.

The flock dissolves into a scattering of individuals.

Piper journeys alone to the furthest periphery of space, to the edge of the galaxy, only to realize that in asserting his individuality he has killed something beautiful - the Wonderbird. So the Wonderbird is an image of the fragility of community, togetherness and tradition.

Perched on a rock on the edge of the galaxy, cold and alone, Piper sings in a quavering voice, singing his small part of the Wonderbird's song, and miraculously his voice carries on the wind, the birds hear him and flock together again, singing as one: the Wonderbird is reborn.

Of course, as an artist I am very much an individual, but the traditional function of the artist was to be a force for renewal in society. It may be right, at certain historical moments to 'rip it up and start again'. It requires courage to do that - and the pioneers of Modernism were certainly brave. But our brave new world, utiltarian, materialistic, increasingly homogenous, seems more and more dystopian. 'Modernism' literally means 'presentism' and nothing can last that rejects the past.

The 'Song of the Wonderbird' is meant as a metaphor for those timeless patterns that unite us all, that can connect past, present and future.

GTP- Have you ever been part of any folkloric activities such as dancing, singing, parading etc? Folk Crafts? Walking and rambling? Do you know of any local to you that you enjoy?

DL- I'm fascinated by the layers of tradition, and the depths of cultural memory around me.

Greenman keystone

This Green Man is above the door of an ordinary 1880's terraced house in East London, but it echoes ancient images of tribal gods from thousands of years ago, like the famous face of the god found at Bath, originally set above a grand temple entrance.

Greenman Roundel

As a writer I try to draw on the archetypal patterns and images of fairytale and myth. I love the idea that something as basic as fear of the dark still dominates our lives, just as it did in the Stone Age. You only have to walk alone in a forest at night for all those ancient fears to crash back into the present day.

Stories are about fear and danger and conflict. Books, films, drama, which we see as 'escapism', are sacred rites of losing ourselves and finding ourselves again. The more we are absorbed in a story the higher we value the experience: a good set-up keeps us on the edge of our seats, a good plot-twist shakes us to the core. We all know when an ending feels satisfying and right, and when it's wrong we feel cheated and angry.

These are ritual patterns, and even in our supposedly secular age, ritual still dominates our lives.

Even the simple act of setting the table for a family meal gives us insights into what beauty is, and how it works. We want things to be 'right' - there are basic rules to observe, rules of symmetry, pattern, cleanliness, that make the table feel like a still point at centre of the whirling Universe.

Formality frames spontaneity. Restraint creates energy. Boundaries generate meaning.

And ritual helps us observe the passage of time - each time we repeat a formal structure we notice the differences, in ourselves and in others: each Christmas my daughter is a bit more grown up, and me and my wife are older - and maybe we're all wiser. But it is the ritual that makes that difference felt. Ritual also helps us capture the transience of life: a 'perfect' Christmas, when everything is 'just right', will never be repeated.

Sorry - it seems I haven't quite answered your original question! What I'm trying to say is that the definition of 'folk' culture can be expanded to anything that has a ritual form, relatively unchanged in generations.

GTP- Do you have any favourite or influential folk stories, songs/folk or world music?

DL- I think the real power of folk-tales is in the imagery. I've been enjoying reading fairy tales to my 4 year old daughter - and images of Puss in Boots, or the gingerbread house in Hansel and Gretel, have the same impact on her as they would have had on a child centuries ago.

I've been writing a long fantasy novel based on a legend from Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain (1136). I like to imagine that those old stories contain more truth than is commonly supposed. Geoffrey of Monmouth was another of the books I discovered as a teenager at my local library. It is the source for the King Lear story, and the King Arthur stories. One chapter is called the Prophecies of Merlin - here is a flavour:

Geoffrey of Monmouth

GTP- The mechanism of Anthropomorphism is key to many world religions and myth-systems, (such as many animistic beliefs) when you use it in your writing/story creation are you aware of connections to any of them?

DL- I grew up in a big Catholic family, but my Dad used to describe himself as a nature-worshipper. He found it easier to relate to nature than people, and he loved birdwatching. (I'm sure that he was somewhere on the autistic spectrum.) The mythographer Joseph Campbell, saw that the transcendent 'sky god' of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, was a desert god, the product of a relatively barren, dry landscape. Cultures in more fertile zones believe in an immanent god, not above nature but hidden within it, a many-faced god whose identity multiplies into a profusion of spirits, demons, nymphs, fairies, etc. haunting every tree and river and lake and hill.

Visiting Japan, I was fascinated to learn more about animism. A sacred waterfall, for example, is the actual god - there is no god 'of' the waterfall, the god is the waterfall.

The same was true of the animism of the ancient Romans, before they fell under Greek influence. Janus wasn't god of the door - he was the door itself, that kept you safe at night. Vesta wasn't goddess of the hearth - she was the actual flame that cooked your supper, and you gave thanks to her before eating supper, just as you gave thanks to Janus for keeping your children safe.

Seeing everyday objects as living beings, with souls and a personality, is how children see the world. I don't think it is as 'primitive' as it might seem. Panpsychism is the idea that everything has some level of consciousness, and it is now being taken seriously by science, as the only consistent explanation for how the entirely ordinary stuff in our heads can think and feel. Ultimately, we may be all no more than a point of view. But what if everything - even your coffee cup - has a point of view, a dim awareness of its stance in relation to the rest of the world? I think that personality and point of view are one and the same. Personality may be the most fundamental force of nature.

I often think about how society would change if panpsychism became the accepted scientific narrative. It might be the big transformation of the 21st century.

GTP- What kind of artworking processes, tools, techniques have you used when creating The Wonderbird? Are they different and specific design choices for The Wonderbird than you utilised for past books?

DL- I have been drawing birds since I was a small child - my Dad used to take me and my brothers to museums where we'd sit with our little sketchbooks making very accurate and un-childlike drawings of stuffed birds.

I drew the birds in Wonderbird freely, in pen, then reversed them out and coloured them with a limited palette of bright colours.

Wonderbird Cover

GTP- The design of the cover of your picturebook, and the format used in The Wonderbird is quite classic, and reminiscent of the design of 60's/70's picturebooks like The Rain Man by Helga Aichinger. Is there anything about the books created in that period that chimes with you?

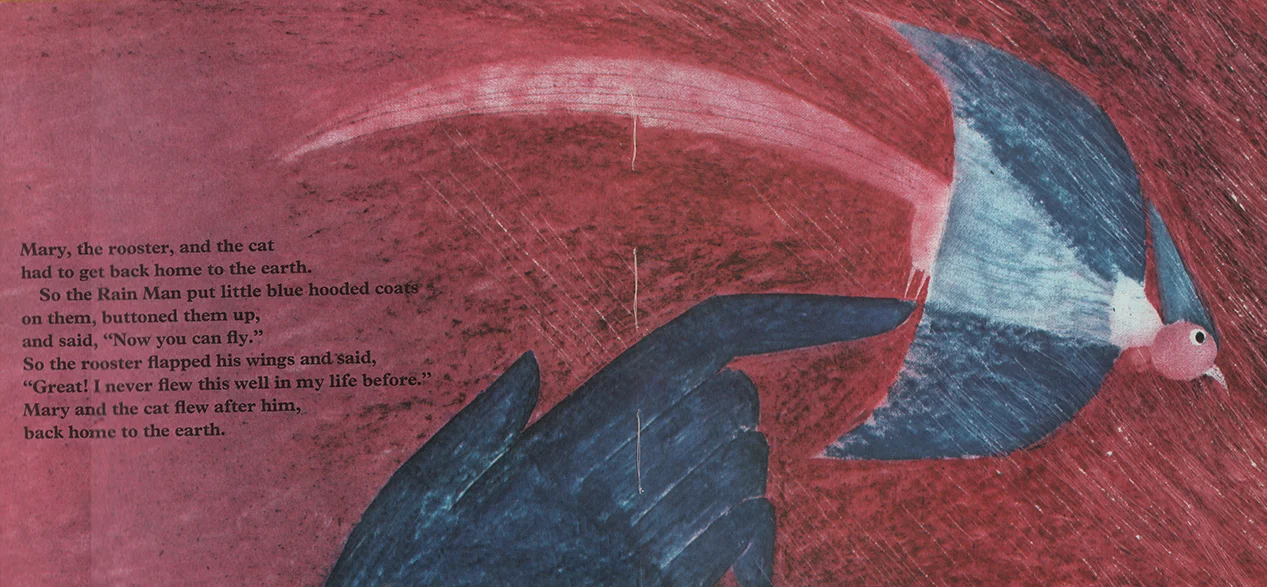

Example- The Rain Man, Helga Aichinger. 1970, Neugebauer Press, Bad Goisern, Austria. UK Publisher Dobson Books.

Example spread- The Rain Man, Helga Aichinger. 1970, Neugebauer Press, Bad Goisern, Austria. UK Publisher Dobson Books.

DL- Yes I suppose the limited colour palette is the main link with 60s picture books? I tend to be influenced more by folk art, medieval art, Indian art etc. than recent illustration. This image was from a recent exhibition of Warli painting at the V&A Museum of Childhood.

Warli painting, V&A Museum of Childhood

GTP- Maybe that 60’s influence is coming more from the graphic design that Orchard Books is using to present your work, reflecting the attitude of a time in publishing when Picture Books were more likely to be poetic in composition and storytelling…

To conclude, many thanks to David for taking the time to think and write so deeply about his work and influences, and for sourcing such fascinating imagery.

Interview by ZEEL.